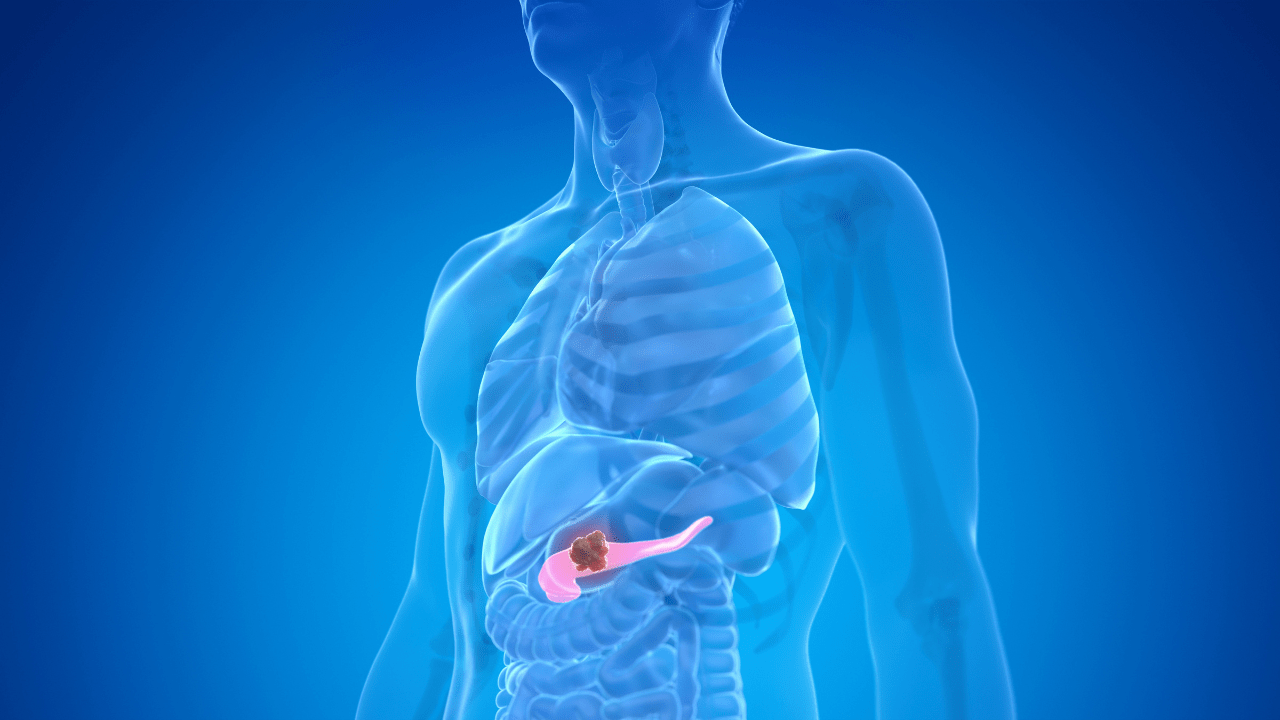

Pancreatic cancer is a type of cancer that originates in the cells of the pancreas, an organ located behind the stomach. The pancreas plays a crucial role in producing enzymes that aid in digestion and hormones, including insulin, which regulates blood sugar.

There are two main types of pancreatic cancer:

- Exocrine Pancreatic Cancer: This is the more common type, accounting for about 95% of cases. It usually begins in the cells that line the ducts of the pancreas and is often referred to as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

- Endocrine Pancreatic Cancer (Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors): This type is much less common and starts in the hormone-producing cells of the pancreas.

Risk Factors:

Several risk factors are associated with pancreatic cancer, including:

- Age: The risk increases with age, with most people being diagnosed in their 60s or 70s.

- Smoking: Cigarette smoking is a significant risk factor.

- Family History: Having a close relative with pancreatic cancer may increase the risk.

- Chronic Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas over a long period can elevate the risk.

- Diabetes: People with long-standing diabetes have an increased risk.

- Obesity: Being overweight or obese may contribute to a higher risk.

Symptoms:

Pancreatic cancer often does not cause symptoms in its early stages. As the cancer progresses, symptoms may include:

- Jaundice: Yellowing of the skin and eyes.

- Abdominal or Back Pain: Pain in the abdomen or back is common.

- Unexplained Weight Loss: Significant weight loss without an apparent cause.

- Loss of Appetite and Digestive Issues: Nausea, vomiting, and changes in bowel habits.

Diagnosis and Treatment:

Diagnosis typically involves imaging tests such as CT scans, MRIs, and endoscopic ultrasound. A biopsy may be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment options depend on the stage of the cancer and may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of these. Unfortunately, pancreatic cancer is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, which can limit treatment options and contribute to a poorer prognosis.

Early detection is challenging, and research is ongoing to improve diagnostic methods and treatment outcomes for pancreatic cancer. If you or someone you know is experiencing symptoms or is at an increased risk, it’s important to seek medical attention for a proper evaluation.

A pancreatic cancer mRNA vaccine

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), which is the most common type of pancreatic cancer, is one of the most killing types of cancer. Even with today’s treatments, only about 12% of people who are diagnosed with this cancer will still be living five years later.

Immunotherapies, which are drugs that help the immune system fight tumors, have changed the way many types of cancers are treated. So far, though, they haven’t worked in PDAC. It’s not been clear if pancreatic cancer cells make neoantigens, which are proteins that the immune system can target successfully.

A group of researchers from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) led by Dr. Vinod Balachandran and backed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have been working on a personalized mRNA cancer-treatment vaccine. It is meant to help immune cells find certain neoantigens on pancreatic cancer cells in patients. The results of a small clinical trial of their new treatment were reported in Nature on May 10, 2023.

The team sent tumor samples from 19 people to BioNTech, a business that made one of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, after surgery to remove PDAC. Gene sequencing was done on the tumors by BioNTech to look for proteins that might make the immune system react. After that, they used that data to make an mRNA vaccine that was unique for each patient. Up to 20 neoantigens were used in each treatment.

Customized shots worked well for 18 of the 19 people who took part in the study. For most people, it took about nine weeks from surgery to getting the first dose of the vaccine.

Before getting vaccinated, all of the patients were given a drug called atezolizumab. An immune checkpoint inhibitor is the name of this drug that stops cancer cells from weakening the immune system. It was then given nine times over a period of months. After the first eight doses, the people in the study also started taking normal chemotherapy drugs for PDAC. They then got a ninth dose to boost their immune systems.

Sixteen of the subjects stayed healthy enough to get at least some of the shots. In half of these patients, the vaccines turned on strong immunity cells called T cells that could find the patient’s specific type of pancreatic cancer. The study team worked with Dr. Benjamin Greenbaum’s lab at MSKCC to come up with a new way to use computers to keep track of the T cells that were made after the vaccination. They looked at the blood and found that there were no T cells that recognized the neoantigens before the vaccine. Only half of the eight patients who had strong immune reactions had T cells that were able to target more than one vaccine neoantigen.

People who had a strong T cell reaction to the vaccine did not have cancer come back by the end of the second year and a half after treatment. People whose immune systems didn’t react to the vaccine, on the other hand, got cancer again in just over a year on average. In one person who had a strong reaction, T cells made by the vaccine seemed to even get rid of a small tumor that had spread to the liver. It looks like the T cells that were triggered by the vaccines kept the pancreatic cancers in check.

“It’s exciting to think that a personalized vaccine could help the immune system fight pancreatic cancer, which needs better treatments right away,” says Balachandran. “It also gives us hope that we might be able to use personalized vaccines to fight other cancers that kill.”

To figure out why half of the people who got personalized vaccines did not have a strong immune reaction, more work needs to be done. The researchers are planning to test the vaccine on a bigger group of people soon.

For what reason did the CEO of Apple die?

Steve Jobs was an American businessman, engineer, and co-founder of Apple Inc. He died on Oct. 5, 2011, after complications from pancreatic cancer. He was 56 years old.

References: Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Rojas LA, Sethna Z, Soares KC, Olcese C, Pang N, Patterson E, Lihm J, Ceglia N, Guasp P, Chu A, Yu R, Chandra AK, Waters T, Ruan J, Amisaki M, Zebboudj A, Odgerel Z, Payne G, Derhovanessian E, Müller F, Rhee I, Yadav M, Dobrin A, Sadelain M, Łuksza M, Cohen N, Tang L, Basturk O, Gönen M, Katz S, Do RK, Epstein AS, Momtaz P, Park W, Sugarman R, Varghese AM, Won E, Desai A, Wei AC, D’Angelica MI, Kingham TP, Mellman I, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD, Sahin U, Türeci Ö, Greenbaum BD, Jarnagin WR, Drebin J, O’Reilly EM, Balachandran VP. Nature. 2023 May 10:1-7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06063-y. Online ahead of print. PMID: 37165196.

Funding: NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI); Stand Up to Cancer; Lustgarten Foundation; Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation; Ben and Rose Cole Charitable PRIA Foundation; Mark Foundation; Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance; Pew Charitable Trusts; Cycle for Survival; Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; imCORE Network; Genentech; BioNTech.