Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious viral infection that primarily affects children, but can occur at any age. It is caused by the measles virus, which is part of the paramyxovirus family.

The COVID-19 outbreak had a lot of effects.

The COVID-19 outbreak made it harder to keep an eye on people and give them vaccines. Millions of children are at risk for diseases like measles because vaccination programs were stopped and immunization rates and monitoring fell around the world.

No country is immune to measles, and places with low vaccination rates make it easier for the virus to spread. This makes cases more likely and puts all children who haven’t been vaccinated at risk.

Despite the COVID-19 outbreak, we need to get back on track and meet regional measles reduction goals. Immunization programs should be improved as part of basic healthcare, and efforts should be sped up to give all children two shots of the measles vaccine. Countries should also set up strong monitoring systems to find protection holes and close them.

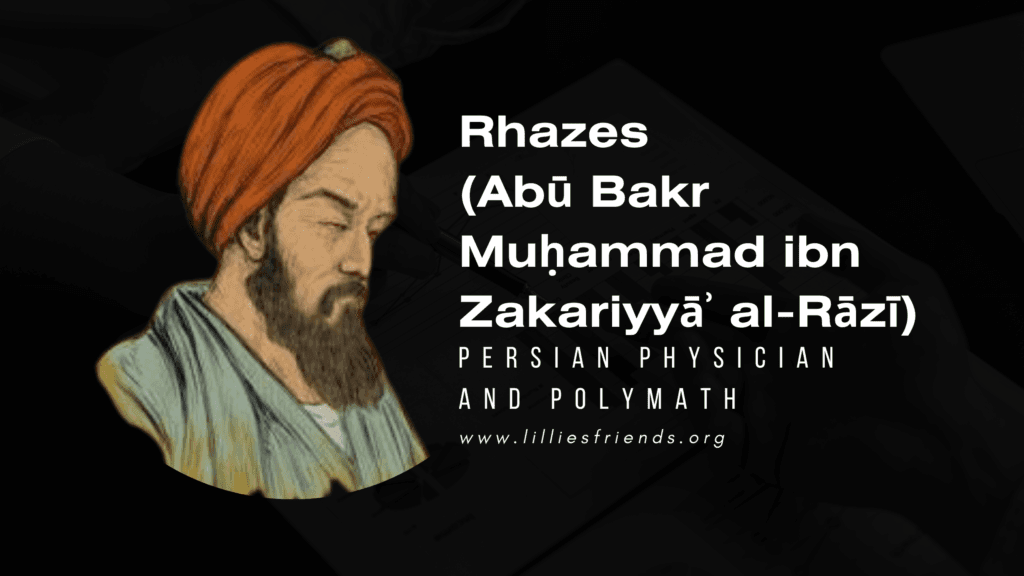

Measles is an ancient infectious disease with a history dating back centuries. Here is a brief overview of the history of measles:

Ancient Origins: Measles is believed to have originated in early human populations and may have first infected humans thousands of years ago. However, it wasn’t well-documented in historical records until more recent centuries.

First Descriptions: The first recognized descriptions of measles date back to the 9th century. Persian physician and polymath Rhazes (also known as Al-Razi) provided one of the earliest known clinical descriptions of measles in the 9th century.

Spread and Impact: Measles has historically been a highly contagious and sometimes deadly disease, particularly when it emerged in populations with no previous exposure. It has caused numerous epidemics and had a significant impact on populations around the world.

What is Measles?

Measles is a virus-caused disease that spreads through the air and is very easy to catch. About eight to twelve days after being infected, you might start to feel sick. The symptoms can last up to two weeks.

Measles is also known as rubeola, the 10-day rash, or the red rash. It’s not like rubella or German measles.

What makes measles different from German measles?

Measles (rubeola) and German measles (rubella) are two distinct viral infections, caused by different viruses, with different characteristics and potential consequences. Here are the key differences between the two:

Causative Viruses:

Measles (Rubeola): Caused by the measles virus, which is a paramyxovirus. German Measles (Rubella): Caused by the rubella virus, which is a togavirus. Severity and Complications:

Measles: Can lead to serious complications, especially in vulnerable populations. These complications may include pneumonia, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), ear infections, and other health issues. German Measles: Generally milder in severity compared to measles. The primary concern with rubella, especially for pregnant women, is the potential harm to the developing fetus if the mother contracts the virus during pregnancy. This can result in congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), which can cause a range of birth defects and developmental problems.

Transmission: Both viruses are spread through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Incubation Period:

Measles: Has a longer incubation period, typically around 10-14 days from exposure to the onset of symptoms. German Measles: Has a shorter incubation period, typically around 14-21 days from exposure to symptoms. Symptoms:

Measles: Initial symptoms include fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes. After a few days, a characteristic red, blotchy rash typically appears, starting on the face and spreading down the body. German Measles: Symptoms can include a mild fever, headache, and a distinctive red-pink rash that typically starts on the face and spreads to the trunk and limbs. Complications for Pregnant Women:

Measles: While measles can be serious for pregnant women, it is not associated with specific birth defects or complications for the fetus. German Measles: Contracting rubella during pregnancy can lead to congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), which can cause a range of birth defects and developmental problems in the baby.

Vaccination:

Both measles and rubella can be prevented with vaccination. The measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine provides protection against both diseases and is typically administered in two doses. Understanding these differences is crucial for prevention, especially for vulnerable populations like pregnant women and those who have not been vaccinated. It’s important to consult healthcare professionals for specific guidance on vaccination and prevention strategies.

Transmission

Measles is one of the most infectious diseases in the world. It can be spread by coughing, sneezing, or taking in the air that someone with measles has swallowed. The virus can spread through the air or on objects that have been affected for up to two hours. Because of this, it is very contagious, and one person with measles can spread it to nine out of ten close friends who haven’t been vaccine. It can be spread by a person who has it from four days before the rash shows up to four days after it does.

When the measles spreads, it can cause serious problems and even death, especially in young, undernourished children. In countries that are almost done getting rid of measles, cases that come from other countries are still a major source of infection.

Some things that can go wrong are:

• going blind

• encephalitis, which is an illness that can cause swelling of the brain and possibly brain damage.

• Severe diarrhea and dehydration from it

• infected ears

• a lot of trouble breathing, like pneumonia.

If a woman gets measles while she is pregnant, it can be dangerous for her and cause her baby to come early and weigh less than usual.

Most complications happen to children under 5 years old and people over 30 years old. Children who are poor, especially those who don’t get enough vitamin A or whose immune systems are weak from HIV or other diseases, are more likely to get them. Measles itself lowers the immune system and can make the body “forget” how to fight off illnesses, leaving children very exposed.

Who is in danger?

Anyone who isn’t immune (hasn’t been vaccinated or was vaccinated but didn’t get immune) can get sick. People who are young and not protected are most likely to have serious consequences from measles.

People still get measles, especially in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. The vast majority of measles deaths happen in countries with low incomes per person or weak health systems that make it hard to immunize all children.

Damaged health facilities and health services in countries going through or healing from a natural disaster or war stop regular immunizations, and overcrowding in living camps makes it more likely that people will get sick. Children who are malnourished or have a weak immune system because of something else are most likely to die from measles.

How to Treat

Measles can’t be treated in a certain way. The person giving care should focus on easing the person’s complaints, making them feel relaxed, and stopping problems from happening.

Fluids lost from diarrhea or vomiting can be replaced by drinking enough water and taking medicines to treat dehydration. It’s also important to eat healthy foods.

Antibiotics can be used to treat lung infections, ear infections, and eye infections.

Everyone who has measles should get two doses of vitamin A pills, each given 24 hours apart. This fixes low vitamin A levels, which can happen even in kids who eat well. It can help keep your eyes from getting hurt or going blind. Vitamin A pills might also cut down on the number of people who die from measles.

Prevention

The best way to stop measles is to get everyone in a community vaccinated. All kids should get a shot to protect them from measles. The vaccine is safe, works well, and is cheap.

The vaccine should be given to children twice to make sure they are immune. In places where measles is common, the first dose is generally given at 9 months of age. In other places, it is given at 12–15 months. A second dose should be given later, typically between 15 and 18 months of age.

The measles vaccine is often given with shots for mumps, rubella, and/or chickenpox, but it can also be given on its own.

Routine measles shots and mass vaccine programs in countries with a lot of cases are important ways to cut down on measles deaths around the world. The measles vaccine has been used for about 60 years and costs less than US$1 per child. In situations, the measles vaccine is also used to stop outbreaks from getting worse. Refugees are especially likely to spread measles, so they should get vaccination as soon as possible.

Combining vaccines makes them a little more expensive, but it saves money on delivery and administration, and most importantly, it protects against rubella, which is the most common infection that can be prevented by a vaccine and can affect kids while they are still in the womb.

In 2022, 74% of children had both shots of the measles vaccine, and 83% of children around the world had at least one dose by the time they turned one. It is suggested that children get two doses of the vaccine to make sure they are immune and stop cases, since not all children are immune after the first dose.

In 2022, regular vaccination meant that about 22 million babies missed at least one dose of the measles vaccine.

Vaccination: The development of the measles vaccine in the mid-20th century marked a significant turning point in the history of the disease. The measles vaccine became widely available and is now administered as part of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine series.

Eradication Efforts: In the 20th century, there were concerted efforts to control and eliminate measles through vaccination campaigns. In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an initiative to eliminate measles worldwide. While measles is not completely eradicated, significant progress has been made in reducing its incidence through vaccination programs.

Measles Elimination in the Americas: In 2002, the Americas region (North and South America) became the first in the world to eliminate measles, meaning that continuous transmission of the virus was interrupted in the region.

Global Vaccination: Despite the availability of vaccines, measles remains a significant global health concern, especially in regions with lower vaccination rates. Outbreaks can occur when vaccination rates fall below the threshold required for herd immunity.

Resurgence and Challenges: In recent years, there have been reports of measles resurgence in some countries due to vaccine hesitancy, gaps in vaccination coverage, and international travel. These outbreaks highlight the importance of maintaining high vaccination rates.

Throughout history, measles has been a significant infectious disease, but vaccination efforts have had a profound impact on reducing its prevalence and associated complications. Public health initiatives continue to focus on achieving global measles elimination and preventing outbreaks through vaccination.